With a recent frost, we thought a trip a few kilometers southward would warm things up a degree or two to make a two day trip over Lunar New Year something a little more memorable. I had had my eye on the foothills of Tainan and the Highway 29 to Namaxia for quite some time, dating as far back as when in was still the Highway 21 to Sanmin. This vacation would be a good opportunity to put this plan into motion.

I met up at Taichung Station with Michael T. and Iris L. to hop the shaky local train down to Longtian in Tainan. We quickly clipped out gear together and found our way along the 171to the Local Rte. 119. We had entertained the idea of hopping on the 84 Expressway for a kilometer or two of less than legal riding, bit the 182-1 detour was enough of a joy, it was worth the extra daylight to skirt through clumps of forest and hills.

For this rider, a tour through the Tainan area, and especially the area on the eastern side of the No. 3 Freeway, is an adventure behind every bend. I rode up ahead scanning every yard, shrine, grave, face, and stump for any evidence of the Siraya indigenous culture on the landscape and I will be discussing it in much greater depth in the near future.

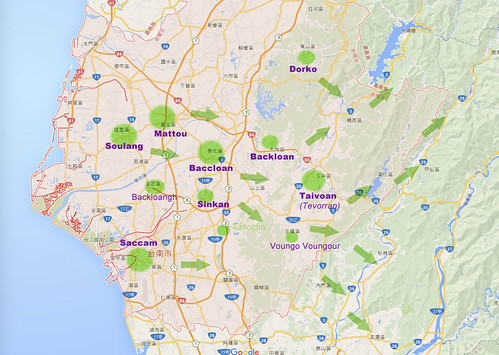

The Siraya are the descendants of the indigenous culture that thrived on the Tainan plain until successive colonial regimes of the Dutch, Chengs, Qing, Japanese and Kuomintang, resulted in the decline of the Siraya as a regional power. With increasing encroachment by Han settlers in the 17th and 18th centuries, some subgroups of Siraya relocated toward the foothills near Taivoan. While most Siraya stayed, acculturated, intermarried and became the local people of Tainan, the Siraya groups which withdrew to the hills attempted to maintain their traditional lifestyle. Now, much of the area to the east of the Highway 3 is still rich with the hints of Siraya culture.

As we rode through a clump of old bamboo on the Route 119, I was on high alert as bamboo palisades were a common fixture of indigenous life on the plains of Taiwan and the existence of thick clumps of bamboo walls is often a sign that a village may have once existed on the site.

A few minutes later I was hollering for everyone to stop. I had spotted the location of an active Siraya temple to Alizu. This temple is an excellent example of the continuation of Siraya forms of spirit worship within a hybridized Buddho-Taoist system of the Han. The indigenous diety had become incorporated into the Buddho-Taoist pantheon similar to the goddess, Mazu. Later, as the Siraya worked toward official tribal recognition, the locals began to embrace the Siraya forms of worship while downplaying the obvious structure of the temple.

I stopped to investigate and record the details of one location where the Siraya are attempting to revive their culture and gain official tribal recognition. According to the government, these people are still considered "Han Chinese".

Traditional village sites as recorded by the Dutch (1624-1662) and the pattern of eastward migration of some subgroups of Siraya. These are the major villages with a few of the more prominent satellite villages marked. Several of the names and locations of satellite villages are still in debate. This map focuses on the Siraya of Tainan does not include Makatao or Hoanya groups of the area.

We rolled along the 182-1 to cross the river to Yujing, where the geology of the moonscape occasionally peeks through holes in the green blanket of jungle that covers the landscape.

\

\After connecting to the Highway 84 from the point that the expressway stops and it becomes a regular highway, we passed Yujing, which is apparently where the mango lives. Signs abound in reference to the, "Home of Mango".

A few twists and dips through the hills and we were soon passing the Nanhua Reservoir. In Taiwan it is always delightful to see so much water in any one place.

At last we were on the Highway 29 to Namaxia.

The gradient is extremely gradual and would be completely doable for most riders and therefore makes an exceptional road for most riders in Tainan looking for easy access to the hills.

As we followed the river toward Namaxia, we passed the village of Xiaolin. The township is home to the descendants of the Siraya who withdrew to the area from the Tainan plain and it had been viewed as a major cultural center for traditional Siraya culture as several of the village elders had working memory of traditional Siraya customs and traditions.

In 2009, water diversion projects combined with the extreme flooding that followed the disintegration of Typhoon Morakot, completely saturated the area causing a rapid collapse of the hillside. The entire village was destroyed within minutes at a tremendous loss of life.

The rebuilding of Xiaolin has not been without controversy.

In the immediate aftermath of the disaster, President Ma Ying-jiu refused to declare a national emergency; a move that would have coordinated rescue and relief efforts between localities and waived off offers of foreign assistance in deferral to China's concerns.

The rebuilding in the aftermath has had even greater repercussions.

According to Chern of the MDRC, of the 19,191 people living in areas identified as more or less unsafe, about 58 percent chose to relocate to more than 3,100 new permanent homes. For this reason, the government’s reconstruction work has centered on the construction of such housing at more than 30 sites. Built on land owned or obtained by the government, the permanent housing construction projects have been organized primarily by NGOs, including the Buddhist Compassion Relief Tzu Chi Foundation, the Red Cross Society of the Republic of China and World Vision Taiwan. Most of the homes have been built, with the rest slated for completion by January 2012. The dwellings are provided free of charge to Morakot survivors, who are allowed to pass them down to heirs, but are not allowed to sell or rent them to others....

Along with rebuilding homes, President Ma has called attention to the need for “spiritual reconstruction” to help Morakot survivors face an uncertain future and assist those who have moved in acclimating themselves to their new environment.Taiwan Today reported at the time:

Under the well-meaning proposal, disaster-affected households in Kaohsiung County’s Namaxia, Taoyuan and Xiaolin townships are to be resettled in new homes constructed on 59 hectares of national land in Shanlin Township. The site was intended for state-run Taiwan Sugar Co., which planned to use it for farming.

The joint project between the government, the Buddhist Compassion Relief Tzu Chi Foundation and Hon Hai Group—Taiwan’s top electronics manufacturing outfit—will see new homes, activity centers and schools constructed for 806 households. The government’s contribution to the project is land, with Tzu Chi responsible for the construction of buildings. Hon Hai is tasked with giving villagers a means to earn a living through establishing organic farms and guaranteeing the purchase of future harvests.

On paper, the idea seems flawless, combining villagers’ needs with a healthy respect for the environment. But as the fog of loss begins to clear from the minds of the victims, many are now thinking clearly and question the plan’s merits. Some have even gone so far as to brand it a hastily patched together hodgepodge that runs roughshod over the ethnicities of survivors and their unique cultural needs.

Alan Tsai, a Xiaolin self-help group spokesman, claims that the proposal forces the Bunun, Tsou and Siraya to live together in an artificial construct. “The Bunun and Tsou peoples traditionally inhabited Namaxia and Taoyuan, upstream of Nanzixian River,” he said. “Further downstream was Xiaolin, where 70 percent of villagers belong to the Siraya tribe.”

Tsai said the plan lumps people from different ethnic backgrounds together in a standardized collective housing complex. “No consideration was made in respect to aboriginal groups’ traditions, ways of life and patterns of social interaction. This could result in the extinction of an irreplaceable aboriginal culture.”

According to local media reports, Tzu Chi wants work on the new homes to get underway as soon as possible and is seeking carte blanche consent from the villagers even before relevant public agencies completed the necessary assessments.

“Villagers are now looking to the government for more reconstruction options and more time to consider how they want to live their lives in future,” Tsai said. “Reconstruction plans should be tailored to the different aboriginal communities and their collective knowledge needs to be solicited.”If we look into this issue a bit deeper, we find the process of reconstruction acts to eliminate local identities and, in essence, continue the process of colonization.

My comments from The View From Taiwan's excellent write up on this trip:

If you look at Michael's photo entitled, "Our Hostel from Above", you can see the plateau that once was a traditional village site. As part of the Japanese campaign to colonize Taiwan and, in the views of the Japanese, "pacify the savages" , the Japanese enacted a civilizing project that began with a military occupation of the mountain areas that had not been under the sovereignty of the Qing. Part of this program involved moving indigenous peoples from their traditional villages into more nucleated clusters at lower elevations and along more accessible routes for a rapid military response. They also stationed police officers in every village to act as an agent of the program to guide indigenes through both coercion and violence to accept the Japanese program. The Japanese colonized by numbers and they brought in scientists and statisticians to better understand their colony. Part of this exercise involved a detailed examination of indigenous peoples on Taiwan. This is the bedrock from which Taiwan's current policy was built. The purpose was to both classify and locate indigenes so that they could be held to boundaries, thus allowing large tracts of land to be allocated for exploitation.

The KMT continued this program under a new government. The KMT equated itself and the Chinese values it crated and espoused to be symbols of modernity. It used Chinese nationalism to promote its civilizing project in indigenous areas. This is evident in several of the name changes. For instance, Namaxia had been called San Min in reference to Sun Yat-sen's Three Principles of the People. Part of their program to weaken indigenous identities in favor of a loyal Chinese nationalist identity...as they feared the stability of the mountain areas and were suspicious over the indigenes cooperation with the Japanese. Housing was one way the KMT government hoped to erode indigenous identities and better allow the state to exploit Taiwan's resources. They moved indigenous peoples from their traditional locations and into concrete box structures to "modernize" them without respect to tradition or the choice of the people. They sought to bring them closer to "civility" by moving them closer to areas where they could be acculturated.

Post Morakot provided an opportunity to further this process as the Ma administration lobbied hard to unilaterally remove indigenous people from traditional areas and bring them closer into the lowlands. Ma expressed his desire to see them living in "modern" concrete houses rather than traditional homes as opposed to allowing indigenes to determine for themselves what they wanted and needed. It is an extension of the colonization we have been seeing from an ethnic nationalist ROC state.

I took a few moments to visit the newly constructed Pingpu Museum--a museum dedicated to the indigenous peoples of the Taiwan plain.

We snaked our way between rocky cliffs toward Namaxia and it began to feel a bit more like the mountains of Taiwan.

One thing that is noticeable to any rider as they travel further up the Highway 29, is the existence of no fewer than three separate highways that have once provided access to the villages near Namaxia.

The overgrown skeletons of asphalt and steel are testament to the forces of nature against the forces of engineering.

As we reached the villages around Namaxia, we could enjoy a few random beams of sunlight and some blue smudges of sky amid the swirling gray clouds.

The scenery was intensely beautiful.

Namaxia is home to villages of the Kanakanavu and Hla'alua (Saaroa) speaking people, who have often been erroneously classified as Rukai.

The first written accounts of these villages come from Dutch records as the VoC, or Dutch East India Company, sent several expeditions into the area between the 1630s and 1650s.

With several villagers succumbing to disease in the 19th century, the villages around Namaxia have been influenced by Bunun speakers who moved into the area.

We arrived at our hostel, where we had an enjoyable dinner over a few refreshing beers.

We also had the opportunity to chat up a few of the locals, such as the artist, Biung Ismahasan and to meet up with Rich Matheson, a Canadian born photographer, who lives near the area and provided some very useful insights into our trip.

The second day was full of promise as the sun came out for an early viewing.

We had to roll back to Maya Village for breakfast, which consisted of two of the largest 蛋餅 I have ever had.

The plan was to climb over the ridge on the Chingshan Agricultural Rd. and return through Dahu on the Highway 3.

We edged higher over the river valley and were soon towering over our hostel.

As we reached the summit, it was evident that we were in Chiayi County, as the roads immediately wend from the sweetest stretches of smooth, black tarmac, to crumbling tracks of ancient asphalt.

It wasn't only the road surface that changed. We went from an area that felt like the mountains of Taiwan, to something resembling the agricultural foothills of central Taiwan.

Tea fields dotted the hillsides and we soon encountered more traffic then we had seen since leaving Jiashian.

I also noted the rise in coffee production as climate change and illegal imports of cheaper Chinese teas have had a detrimental effect of Taiwan's lucrative tea production.

A road closure diverted our posse over a short kilometer-long detour, which proved to hold some wonderful surprises.

We were soon thundering down the mountain at some really exciting speeds.

We were having way too much fun on the descent for the amount of work we had put into climbing.

Before long we were cruising back toward Yujing on the Highway 3 along the Tsengwen Reservoir.

The route along the three consisted of multiple series of rollers and a few pitched climbs. I was feeling excellent and charged ahead to enjoy the contours of the land.

At Yujing we decided to follow the Highway 20 to Xinhua and catch the train back to Taichung at Xinshi.

We kept a respectable pace as the chill from the windy plain reminded us of the appropriate season.

We bagged up, and enjoyed the heated bike car on our way northward, concluding our adventure to Namaxia.